Often, political pundits and the media blame voters for not turning out to vote. Just recently, Samantha Bee slammed the 12% voter turnout in the Los Angeles mayor race. Many find it easy to point to voter apathy and lack of civics education as the cause of dismal voter turnout. However, there is a major factor to low voter turnout that is often left out of the conversation: the timing of elections, especially for places that hold runoff elections.

FairVote studied the effect of a city that consolidated its runoffs. Until 2003, the city of San Francisco held its elections in a November and December runoff cycle. What we found is that prior to the introduction of ranked choice voting (RCV), many voters did not participate in the second round of voting in December, which is called a runoff election. In San Francisco – the median turnout decline for local runoffs between 2000 and 2003 was 39.5%, meaning just three in five voters who voted in the first round of voting turned out in the decisive runoff round.

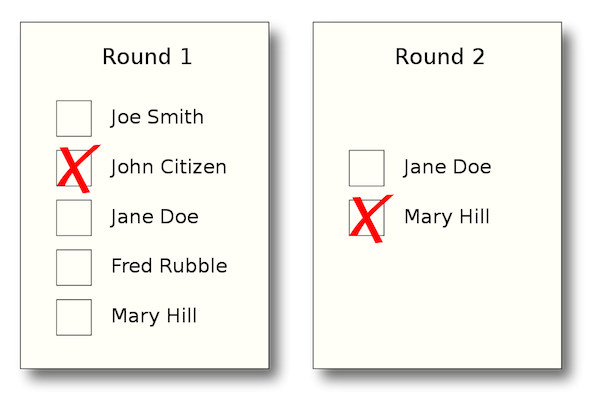

Under RCV, far more voters participate in one decisive election, rather than two elections. RCV gives voters the freedom to rank as many candidates as they want in order of choice. All first choices are counted and if any candidate has a majority of the vote (50%+1) they win, just like any other election. If no candidate has a majority, an instant runoff starts. The candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated. Voters for that candidate have their vote instantly count for their next choice in the race. This process continues until a candidate receives a majority of votes and is declared the winner.

FairVote found that the median percentage of exhausted ballots (ballots that do not count in the final round) in the 24 RCV races needing multiple rounds was just 13.2%, meaning that 86.8% of voters who turned out had their ballot count in the final, decisive, round. This shows us that when and how we vote has a tremendous impact on how representative our elections are. With RCV, voters can cast a ballot and indicate a runoff candidate of choice, all in November, when turnout is highest.

RCV makes more votes count and boosts the representativeness of winners as well. In runoff elections, the average winner won the runoff with 7% fewer votes than the first round leader. The average winner in an RCV election increased his or her vote total by nearly a third of their original vote (32%) in between rounds. By courting second and third choice votes, candidates have the opportunity and incentive to connect with a wider span of voters.

Furthermore, in RCV elections, voters make fewer mistakes. The number of ballots invalidated due to overvotes (voting for more than one candidate or giving the same ranking to multiple candidates) and undervotes (not voting for any candidates) is lower under RCV. On average, overvotes and undervotes combined made up 13.5% of votes in the first round of a runoff in San Francisco between 2000 and 2003. Under RCV, first round overvotes and undervotes have averaged 9.5%. This indicates that voters understand RCV well.

FairVote California is currently working with California community groups and volunteers to bring RCV to their cities. Want to make your city’s elections more representative? E-mail us at [email protected].

To see the full report, click here.

Be the first to comment

Sign in with

Facebook Twitter